What U.S. action in Venezuela Teaches About Second Citizenship, Relocation, and Timing

Permission Decay as the Threat. Option Geometry as the Response

In the previous piece, I argued that Venezuela should not be understood as a regional crisis, but as a signal—specifically, a signal about how American power is now being exercised, and what that shift implies for the international system more broadly. I won’t re-litigate that argument here.

This piece starts where that one ends.

Because once you accept that analysis, the harder—and more consequential—question follows naturally:

What does this mean for someone trying to keep their family and capital out of the blast radius?

The core lesson is not that Venezuela is unstable, or that American gunboat diplomacy has returned. The lesson is that permission is becoming the primary instrument of power—and permission does not fail like a bridge.

It fails like a bureaucracy.

Most people intuitively grasp that as the United States becomes less tethered to justification and accountability, the rest of the world will react. And most understand that those reactions won’t be costless. What’s harder to see is how those costs arrive—how they propagate through systems that still look functional, and why people don’t recognize the failure until options have already narrowed.

In a decaying-permission environment, the danger isn’t that borders suddenly slam shut. It’s that the systems you rely on for mobility—the ability to secure residency, renew status, access banking, move capital, enroll children, and travel on documents that remain technically valid—begin to harden at different speeds.

Americans grew up in an era where mobility was assumed. Banking was assumed. Administrative predictability was assumed. If something took longer than expected, it was an inconvenience—not a warning. The default belief was that rights were usable, permissions were stable, and if you needed to leave, you could always do it later.

That assumption is exactly what permission decay punishes.

Mobility is not a single decision. It is a sequence of permissions that must all remain true at the same time: permission to enter, to remain, to renew, to bank, to move capital, and to keep a household legal and functional while doing all of the above. When one degrades, it pulls on the others. Complex systems fail not through dramatic rupture, but through accumulated constraint.

Aviation provides a useful way to think about this—not because it is dramatic, but because it is a domain where model accuracy matters more than confidence.

In aviation accidents, the aircraft is often flyable until very late in the sequence. Engines work. Controls respond. Procedures exist. What fails first is not the machine, but the mental model operators are using to interpret what’s happening. Instruments disagree. Automation disengages. Pilots continue applying inputs that made sense moments earlier but no longer match reality. By the time the mismatch is recognized, the window for recovery has narrowed or disappeared.

The lesson aviation teaches is not “mistakes are fatal.”

It’s this: by the time you know your model is wrong, reversibility may already be gone.

NTSB reports repeat this pattern relentlessly. Not incompetence. Not recklessness. Delayed recognition inside systems that still appear to function.

Global mobility fails the same way.

People do not get trapped because borders close overnight. They get trapped because permissions degrade unevenly, signals conflict, and they continue acting as if yesterday’s assumptions still apply.

This is why thinking “just get a second passport” is not a plan. It’s a credential. In a tightening system, credentials are often the last thing to become operational—and the first thing to give people false confidence. It’s the equivalent of trusting that everything is fine because the instruments still light up.

Maybe it is.

Or maybe the recovery window is already closing.

This piece is about knowing the difference.

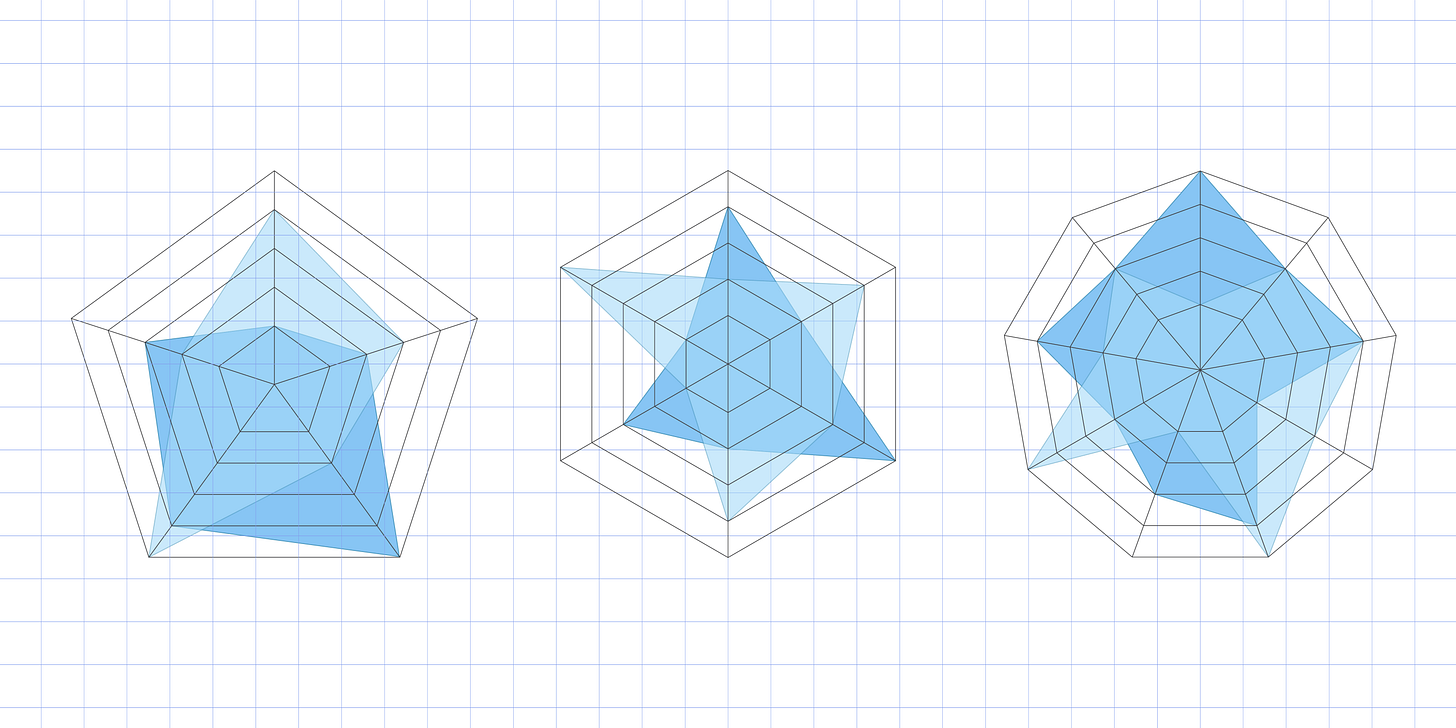

More precisely, it’s about option geometry: how your set of feasible moves changes as permissions decay, and what sequencing preserves degrees of freedom before urgency is imposed on you.

The Geometry of the Problem: Optimizing Under Three Competing Risks

Once permission decay is the operating condition, mobility planning stops being about preference and becomes an exercise in optimization under constraint.

You are not trying to eliminate risk. You are trying to balance it.

Under a discretionary system, three risks dominate all others—and they cannot be minimized simultaneously:

Access risk — loss of the practical ability to enter, remain, bank, transact, enroll children, or function while moving.

Execution risk — failure mid-plan due to slipping timelines, tightening discretion, frozen capital, or assumptions breaking under ambiguity.

Identity risk — exposure created by who you are on paper: nationality, passport, tax citizenship, sanctionability, political association.

This is not a philosophical problem. It is a geometry problem.

You can aggressively reduce one of these risks at a time. When you do, the other two expand. Anyone promising a clean solution to all three is either naïve or lying.

The real question is not which risk matters most in the abstract, but which risk must be minimized first in order to preserve freedom of action as the system hardens.

The answer is almost never the one people want.